The Hidden Bottleneck in AI: Why Your Model's Performance is Capped by 'Label Convergence'

Since the emergence of ChatGPT in 2022, I’ve had the impression that AI has truly entered the mainstream. This wave included a host of other useful products like DALL-E for image generation, Claude for coding assistance, and DeepL for machine translation. These systems, broadly categorized as generative AI, create new content for a user who then typically verifies the result; a human remains in the loop.

In contrast, fields like autonomous driving seem less present in the public eye now. Why is that? We don’t see fleets of self-driving cars on our streets, so the problem is far from solved. These systems are of a different type called discriminative AI. In the research community, they were the primary drivers of the deep learning revolution between 2012 and 2015, dominating challenges in image classification and object detection.

So, why has the focus shifted? These technologies are incredibly useful, with applications ranging from medical imaging and advanced manufacturing to assessing the structural integrity of bridges and dams.

In this article, I want to explore the reasons for this perceived stagnation. I’ll present my perspective on the current state of the field, backing it up with empirical analysis from my recent peer-reviewed publication. My goal is to describe these concepts so that non-technical readers can follow along, while the more technical audience can gain a deeper understanding by referring to the full paper which I presented March 2025 at WACV.

The Teacher, the Student, and the Contradiction

The best discriminative models rely on supervised learning, which means they learn from data labeled mostly by humans. This labeled data acts as a teacher for the model, which is the student. In a perfect world, the teacher is precise and clear. However, sometimes the task is difficult, and the teacher might make a mistake or not be 100% accurate.

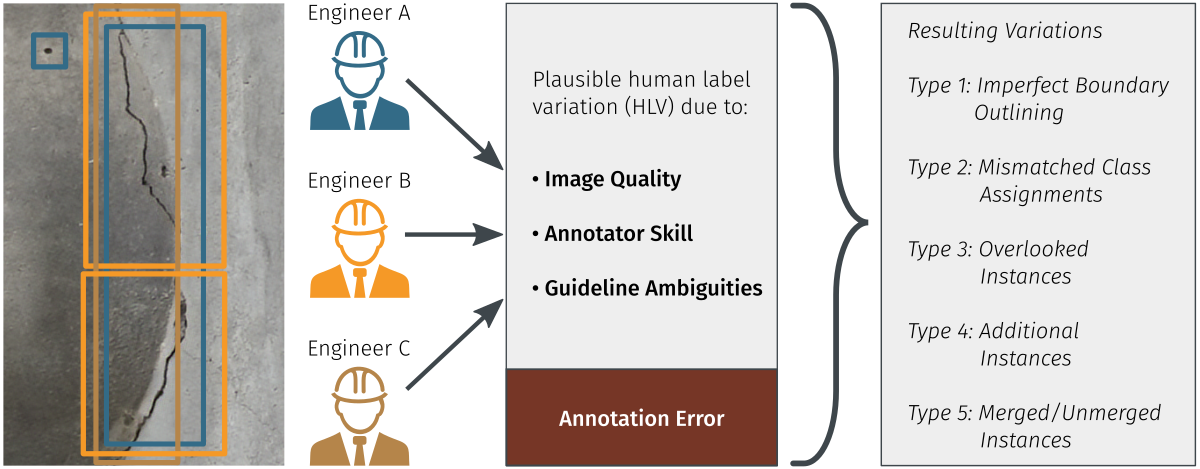

For large datasets, it’s a given that multiple annotators (teachers) are involved. What happens when these different teachers provide various interpretations of the same task? This can happen because the task is inherently ambiguous, multiple interpretations seem reasonable, or for other reasons.

Which teacher’s opinion should the student follow? A neural network faces this exact dilemma. When the teachers’ explanations contradict each other, the model will inevitably get a “clap on the finger” from one of them, as its prediction won’t align with that teacher’s interpretation. I refer to this type of annotation variations as contradictory annotations.

This has a major impact on two stages:

- Model Training: If a model has a high capacity (meaning it’s very large), it can overfit by learning the different interpretations from different annotators. If one group of annotators with a specific convention is much larger than others, the model will likely learn their interpretation as the “correct” one. While research into handling noisy labels offers some solutions, they don’t fully solve the problem.

- Model Evaluation: This is where the issue becomes much grimmer. No training technique can help here. Imagine you have a test set to evaluate a “perfect” dog and cat classifier. But in your test data, some dogs are incorrectly labeled as cats, and vice versa. Even though your classifier makes perfect predictions, the performance report will say it’s not 100% accurate; due to the errors in the labels themselves.

This leads to a concept I call label convergence: the highest achievable performance a model can reach - at least on this flawed test data, which is inherently limited by the contradictory annotations within the test data. It defines a hard upper bound on accuracy that is imposed by the data, not the model.

Just How Big is the Problem?

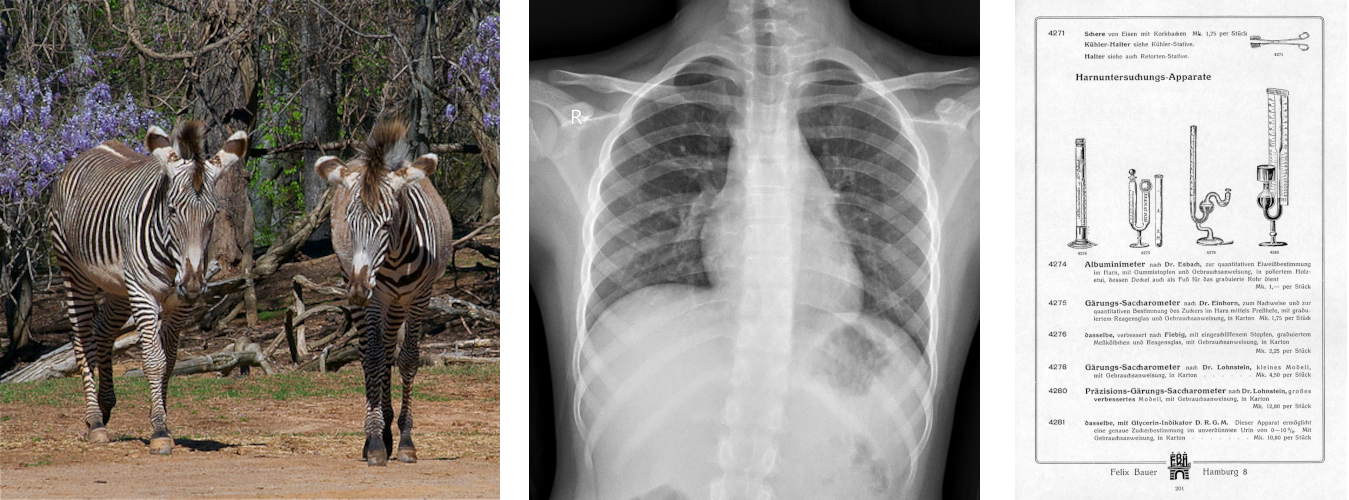

Is this just a theoretical issue, or does it affect real-world benchmarks? To find out, I analyzed several widely used datasets from multiple domains, including LVIS (general objects), VinDr-CXR (medical imaging), and TexBiG (document analysis).

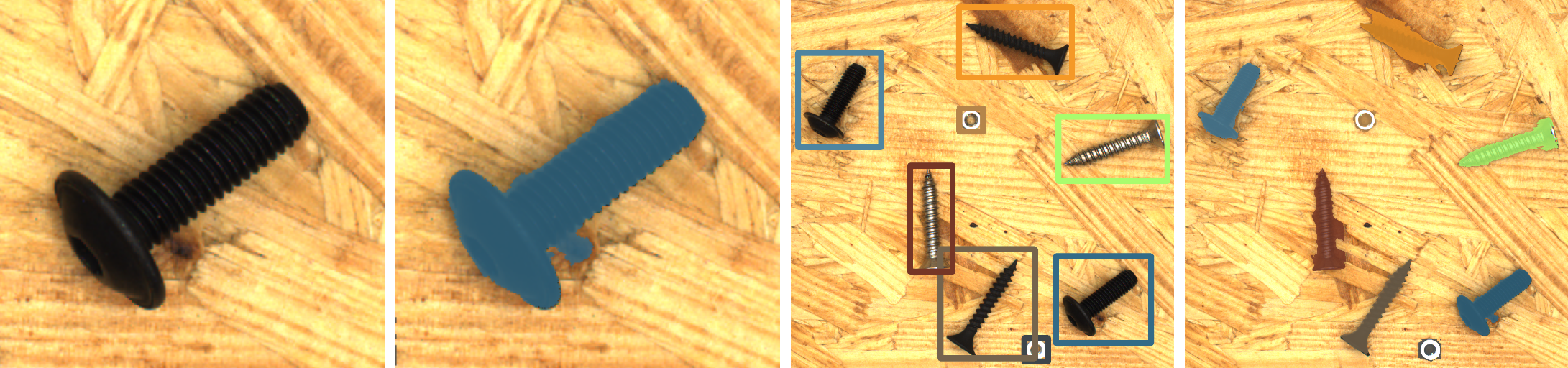

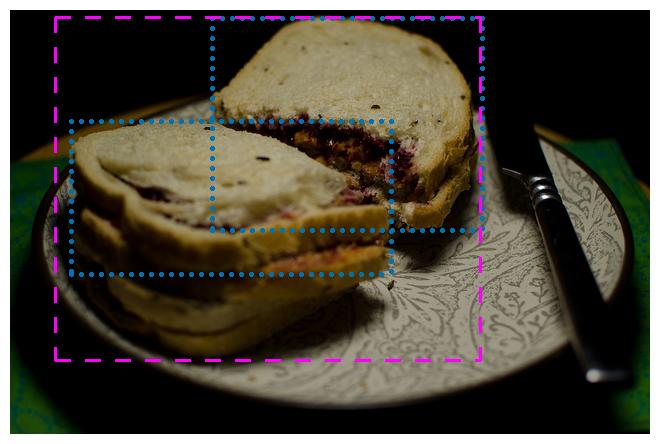

These datasets share a crucial property: each image was annotated by at least two different people (as shown in the toy example in Figure 2). This allows us to see just how much the annotators disagree. The short answer: the differences are significant.

Let’s use the popular LVIS dataset as an example. It has two annotators per image in its consistency subset. In a perfect world, they would produce identical annotations. However, if we treat one annotator as the “ground truth” and the other as a “prediction,” the resulting performance score (mAP) is not 100. Instead, it’s approximately 68.

This is the label convergence threshold for LVIS. It means that no matter how perfect your model is, you can’t reasonably expect it to score much higher than 68 mAP on this test set with current evaluation practices. The performance is capped by the inconsistencies in the labels themselves.

What This Means for Real-World AI

This isn’t an isolated issue confined to academic datasets. As referenced in my paper, numerous studies confirm that label variation is a pervasive challenge affecting datasets across all domains, including those used in industry. For any business aiming to integrate robust and reliable vision systems, understanding the following implications of label convergence is therefore critical:

- The Performance Ceiling: Companies might be wasting significant resources trying to improve a model’s performance by a few percentage points, not realizing they are already pushing against the ceiling set by the dataset’s quality.

- Misleading Benchmarks: This changes strategy. A model scoring 65 mAP might seem average, but if the label convergence threshold is 68 mAP, the model is actually performing exceptionally well relative to the data. The focus should shift from model-centric to data-centric improvements.

- Safety and Reliability: For safety-critical systems, the gap between performance on a flawed test set (in-vitro) and real-world performance (in-vivo) is crucial. Not understanding the data’s inherent ambiguity can lead to misplaced trust in a model’s capabilities.

Pathways to a Solution

To address this challenge, I propose a three-pronged approach based on my research:

- Improve Annotation Quality: This is the most obvious solution. We must implement better annotation guidelines and training to reduce errors and variability. This is especially crucial for test data, where consistency is key for accurate evaluation.

- Include Multi-Annotated Data: Since labels will likely always contain some variation, datasets should include a subset of images annotated by multiple people. This makes the issue of inconsistency visible from the start and allows us to measure it.

- Update Evaluation Methods: We need to rethink how strictly we judge annotations. Instead of trying to eliminate all noise from test sets, we can use the concept of label convergence as a realistic measure of a task’s inherent ambiguity. This leads to a more flexible and practical assessment of model performance.

If you want to dive deeper into the methodology, analysis, and results, feel free to check out the full paper. To experiment with the code used for the label variation analysis, you can use the FiftyOne Plugin developed for this research.